Tis the season…not for jolliness…but for annual forecasting. Countless companies spend the month of December frantically closing out the current year, while scrambling to codify goals for the fiscal year ahead. So, for many small-scale SaaS businesses, this is decidedly NOT the most wonderful time of the year. Rather, when it comes to financial planning and analysis, it can be a time of feast or famine. Famine in this case is represented by simply not doing any intentional planning. A surprising number of small software companies don’t share fiscal goals with their teams, or even set formalized financial plans whatsoever. Feasting, in this case, occurs when a leader’s eyes are bigger than their mouth, resulting in an unreasonably aggressive growth plan based on exuberant hope more than rational thought. Perhaps this is less like feasting, and more like binge-eating junk-food (in that it is based on impulse, offers a temporary jolt, induces sickness soon after, and is terrible health-wise in the long-term). But neither of these extremes is necessary; and a thoughtful plan does not require gobs of bureaucratic process (one of the primary excuses offered for this feast / famine dynamic). Rather, we’ve seen that the simple concept of triangulation can efficiently produce the building blocks of an informed financial plan that balances multiple perspectives on the business. Here’s how it works:

First thing first, this approach focuses overwhelmingly on setting the top-line goals for a business. The long-pole in the financial planning tent is this top-line goal (also known variously as: revenue, bookings, ARR, and sales). This is because sales performance ultimately dictates the money flowing into the business and highly influences the expense levels the business can sustain. Note: admittedly this is more nuanced in businesses with outside funding, but eventually holds true as they mature toward cash-flow breakeven. Bookings are also the most highly variable / least-controllable aspect of any plan, as discussed in this prior post; and getting the top-line goal wrong can unleash a cascade of pain throughout the entire business. For these reasons, setting an appropriate top-line goal is the critical step in developing a sound plan. The reality is, that this goal must be ambitious enough to please financial stakeholders, realistic enough for the team to execute with confidence, and based credibly on relevant historical data (while also not being shackled to the past). A tall order, indeed.

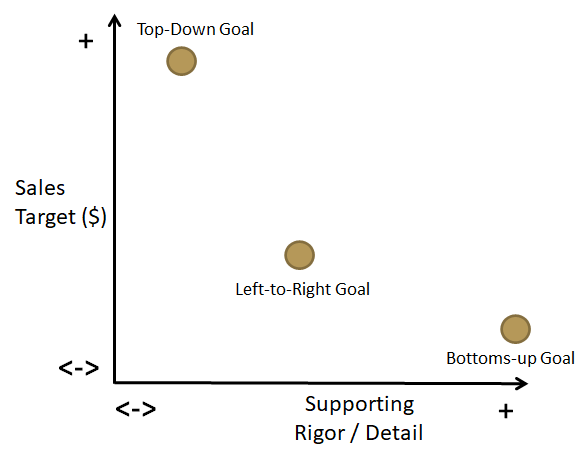

To ultimately arrive at an appropriate goal, we like to start by pulling together three different top-line targets based on three distinct views into the business. Later we’ll compare / contrast / compromise across the three resulting targets, hence the term triangulation. The three perspectives in play are (1) top-down, (2) left-to-right, and (3) bottoms-up, as follows:

Generally speaking, Left-to-Right tends to be the middle-child in our family of goals — neither the aggressive hyper-achiever, nor the black-sheep slacker — just…meh. (Note: this last statement comes from a card-carrying middle-child).

Bottoms-Up: This approach constructs a bookings goal from the bottom up and represents the perspective of the person / people responsible for driving day-to-day sales results (e.g. CRO, VP of Sales, VP of Marketing). This perspective starts from $0 on day 1 of a fiscal year and assumes “nothing happens until someone sells something.” More mechanically, it establishes a bookings forecast from its component parts by building up a notional population of representative sales deals across a time-period. This approach tends to incorporate multiple inputs into detailed models, including:

The resulting forecast from such an approach tends to be quite conservative, sometimes prompting accusations of sandbagging by its advocates. Almost without fail, this will be the lowest among our trio of prospective top-line targets.

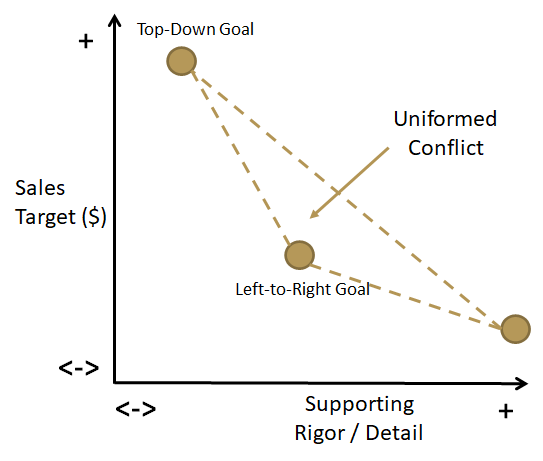

Triangulating: Simply quantifying each of these different perspectives is certainly a step toward a more inclusive and informed top-line goal. But a bit more work at this point is what yields the real progress. The truth is that the three different methodologies produce widely divergent results, both in terms of target figures and the rigor used to arrive at them, so compromise is necessary. Graphically, these could be plotted like this.

Each goal has its own shortcomings, and none of these goals tends to unilaterally offer an ideal bookings target. Without further discussion, these different data points simply shine a light on the misalignment that commonly exists across the various stakeholders. This can look like this:

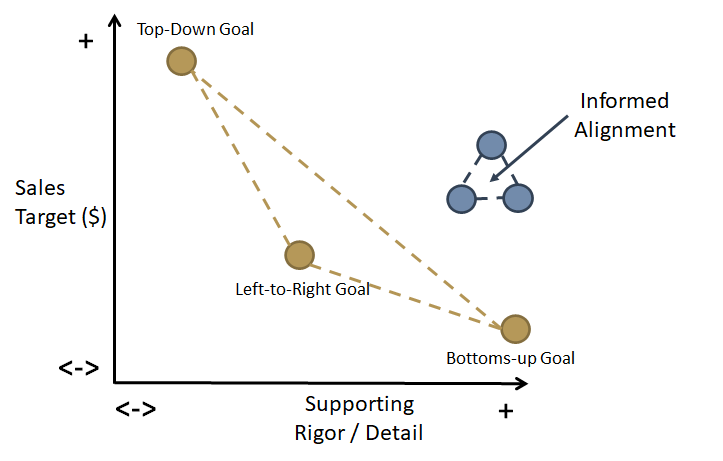

But these inputs also provide the forum for an interactive discussion around the drivers of each. Optimally, organizations can move beyond this zone of Uninformed Conflict simply by asking pointed questions of each goal:

This exercise forces people out of their default perspectives and drives productive (albeit, often uncomfortable) discussions. Inevitably, this drives more informed goal-setting and better alignment across the business…and quite frequently, it helps move the top-line goal up and to the right in our now-familiar graph:

Conclusion: The top-line goal is critical to annual planning efforts. To be fit for purpose, it must balance ambition, credibility, and executability. Only by clearing this bar will it fully serve its multifaceted purpose: to please optimistic financial stakeholders, satisfy the inherent skepticism of internal number-crunchers, and pass the “red-face test” among the troops. Admittedly, this is only a start; and many other components are needed to really nail annual planning. But getting this goal right is a great foundation around which to build; and triangulating across these multiple perspectives is a simple way to inform this process. Plus, doing so is a good way to make the New Year something really worthy of celebration by all stakeholders.